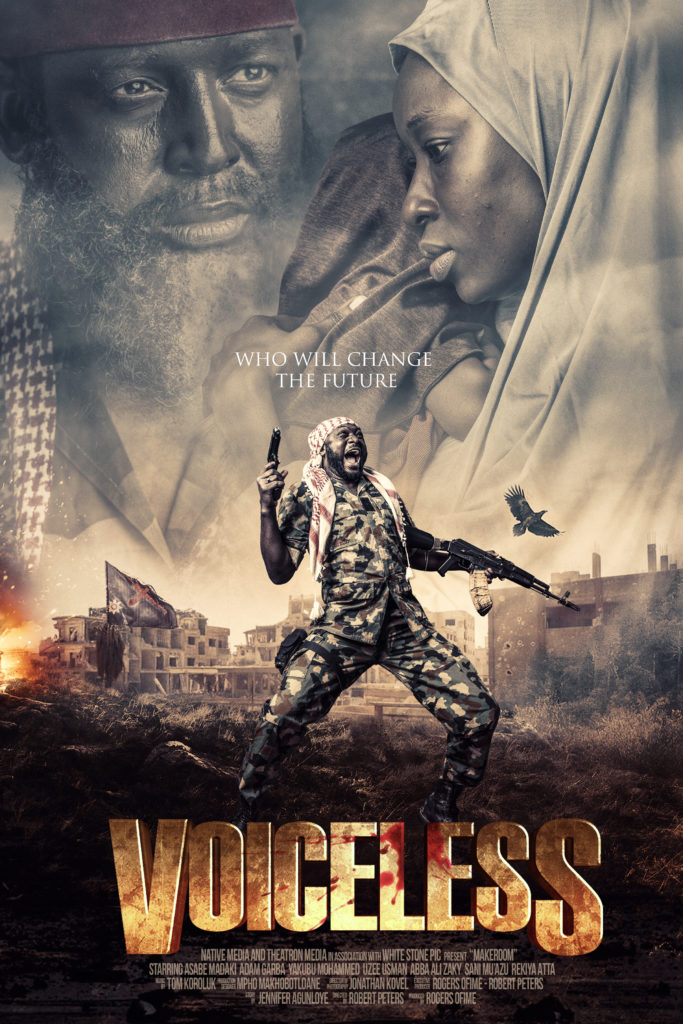

BEST PICTURE

VOICELESS (Nigeria) – WINNER

NOMINESS:

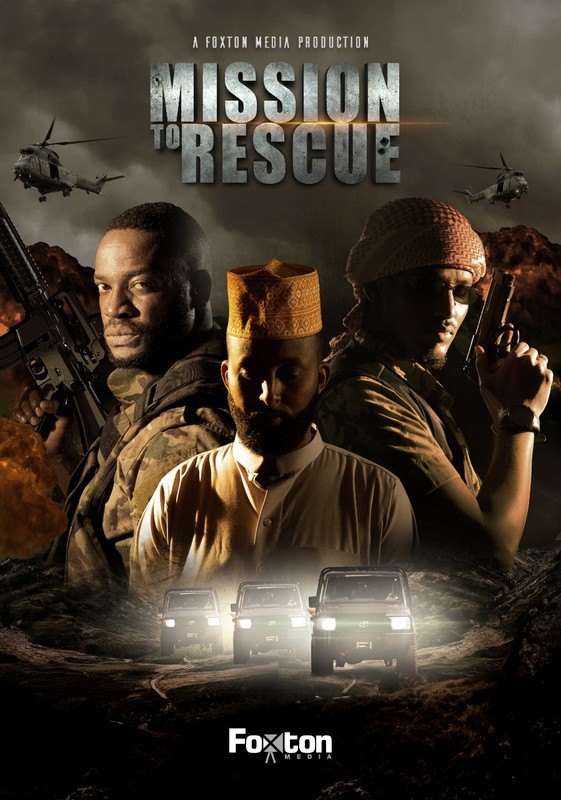

- MISSION RESCURE (Kenya)

- A DANCE TO FORGET(Nigeria)

- HEROES OF AFRICA (Ghana)

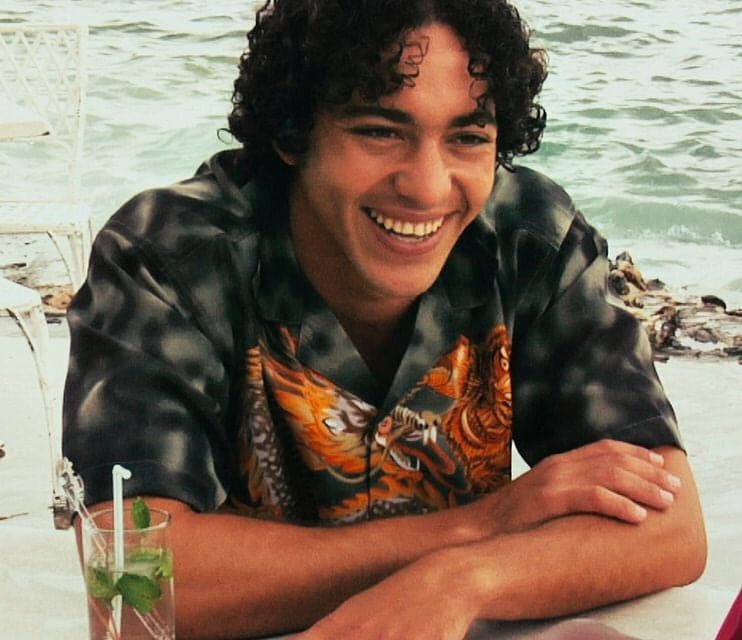

BEST ACTOR MALE

JORGE LUIS CASTRO Movie OCEAN (Russia) WINNER

NOMINESS:

- ADAM GARUBA the movie VOICELESS (Nigeria)

- SEUN AKINDELE Movie DESPERATE PROPOSAL

- BERNARD ADUSE POKU Movie HEROES OF AFRICA (Ghana)

BEST ACTOR FEMALE

UFUOMA MCDERMOTT Movie MR & MRS OKOLI (Nigeria) WINNER

NOMINESS:

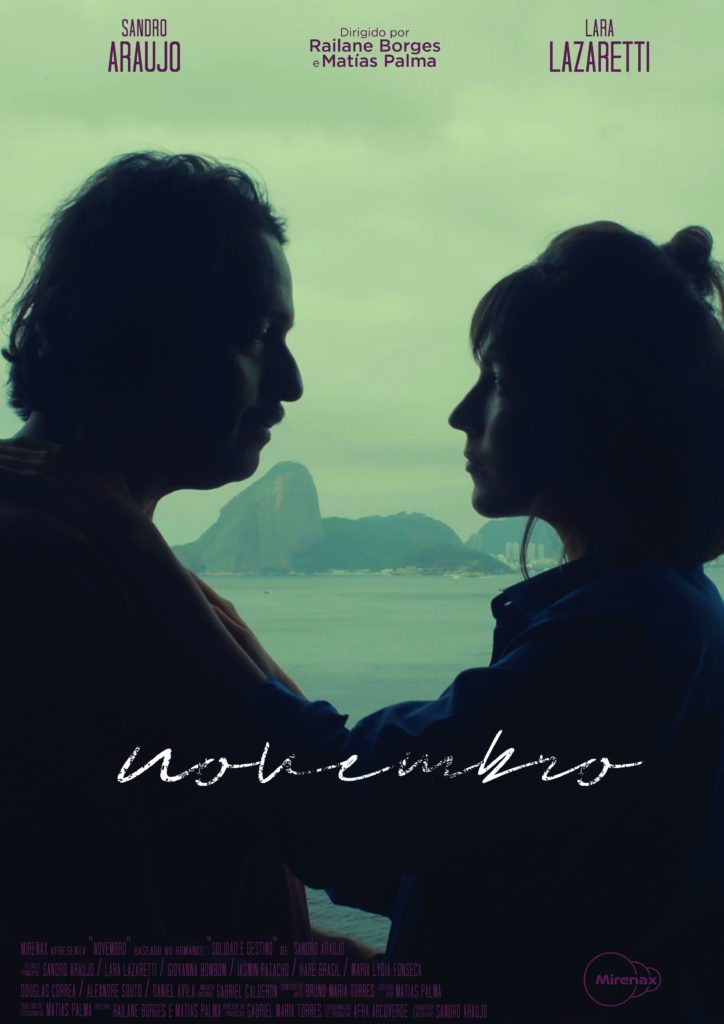

- LARA LAZARETTI Movie NOVEMBER (Portuguese Brazil)

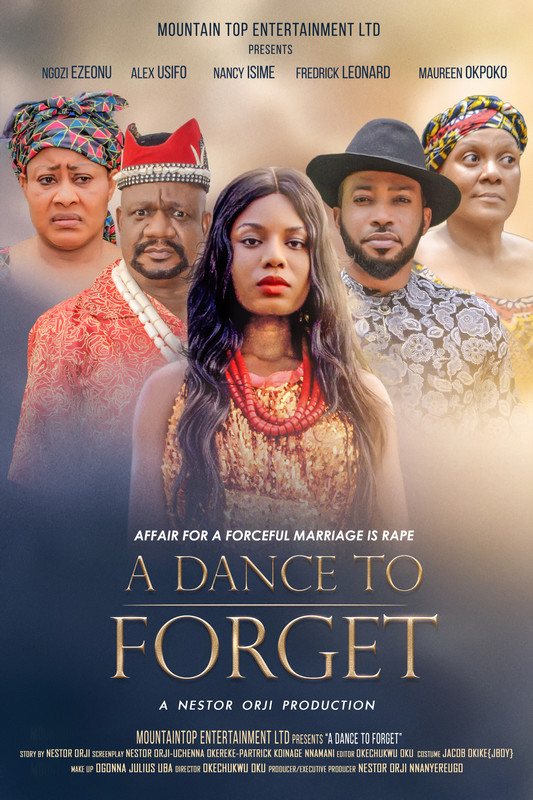

- NANCY ISIME Movie A DANCE TO FORGET(Nigeria)

- ASABE MADAKI Movie VOICELESS (Nigeria)

BEST SUPPORTING ACTOR MALE

FREDERICK LEONARD Movie VENDETTA (Nigeria) WINNER

NOMINESS:

- TONY AKPOSHERI Movie Mr & Mrs Okoli

- NANJIE RAMESH Movie BROKEN POT (Cameron)

- SANI MU’AZU Movie VOICELESS (Nigeria)

BEST SUPPORTING ACTOR FEMALE

NGOZI EZEONU Movie A DANCE TO FORGET (Nigeria) WINNER

NOMINESS:

- YANA IVANOVA Movie GRAND CANCAN (Russia)

- REKIYA ATTA Movie VOICELESS Nigeria

- MA-BI ETONGO CELESTINE Movie BROKEN POT (Cameroon)

BEST DIRECTOR

ROBERT PETERS Movie VOICELESS Nigeria – WINNER

NOMINESS:

- GILBERT LUKALIA Movie MISSION TO RESCUE (Kenya)

- FRANK GHARBIN Movie HEROES OF AFRICA (Ghana)

- MIKHAIL KOSYREV-NESTEROV Movie OCEAN (Russia)

BEST SCREENPLAY

JENNY AGUNLOYE Movie VOICELESS Nigeria – WINNER

NOMINESS:

- KOSYREV-NESTEROV Movie OCEAN Russia

- NAJID ALFRED TOOFE, STANFAME AJALAJA Movie MR & MRS OKOLI Nigeria

- FRANK GHARBIN Movie HEROES OF AFRICAN Ghana

BEST CINEMATOGRAPHY

VICTOR OMBOGO Movie MISSION TO RESCUE – Kenya WINNER

NOMINESS:

- JONATHAN KOVEL VOICELESS – Nigeria

- OLEG LUKICHEV Movie OCEAN – RUSSIA

- VINCENT BAFFOUR Movie HEROES OF AFRICA – Ghana

BEST STORY

HEROES OF AFRICA – Ghana WINNER

NOMINESS:

- OCEAN – Russia

- BROKEN POT – Cameroon

- VOICELESS – Nigeria

BEST CAST DIRECTOR

HEROES OF AFRICAN – Ghana WINNER

NOMINESS:

- OCEAN- Russia

- VOICELESS – Nigeria

- MISSION TO RESCUE – Kenya

BEST FILM EDIT

VOICELESS – Nigeria- WINNER

NOMINESS:

- NOVEMBER – Brazil

- MR & MRS OKOLI – Nigeria

- MISSION TO RESCUE – Kenya

BEST SOUND

HEROES OF AFRICA Movie from Ghana – WINNER

NOMINESS:

- VOICELESS – Nigeria

- MISSION TO RESCUE- Kenya

- NOVEMBER – Brazil

BEST PRODUCTION DESIGN

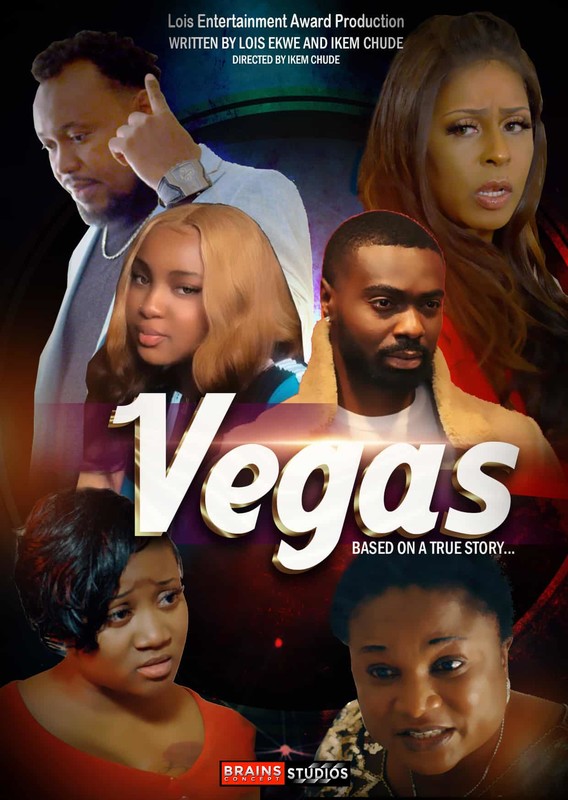

VEGAS – USA- WINNER

NOMINESS:

- VOICELESS – Nigeria

- A DANCE TO FORGET – Nigeria

- OCEAN – Russia

BEST ORIGINAL SCORE

NOVEMBER – Brazil – WINNER

NOMINESS:

- VOICELESS – Nigeria

- A DANCE TO FORGET – Nigeria

- DESPERATE PROPOSAL – Nigeria

BEST ORIGINAL SONG

A DREAM TO FORGET – Nigeria – WINNER

NOMINESS:

- OCEAN – Russia

- NOVEMBER – Brazil

- TWISTED – Nigeria

BEST MAKEUP COSTUME

HEROES OF AFRICA – Ghana – WINNER

NOMINESS:

- DESPERATE PROPOSAL – Nigeria

- PIOUS LOVE- Nigeria

- A DANCE TO FORGET- Nigeria

BEST VISUAL EFFECTS

MISSION TO RESCUE- Kenya – WINNER

NOMINESS:

- OCEAN – Russia

- JUDAS KISS – Uganda

- VOICELESS – Nigeria

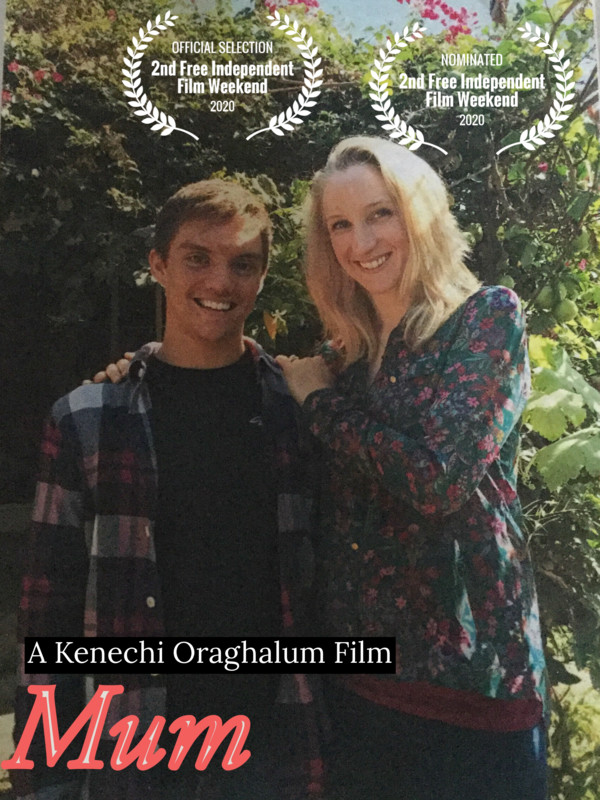

BEST SHORT FILM

MUM Movie from by Kenechi Oraghalum USA – WINNER

NOMINESS:

- BROTHERLY Nigeria

- ARIZONA 1878 Spain

- CLICHÉ – REFLECTION OF A SILHOUETTE Denmark

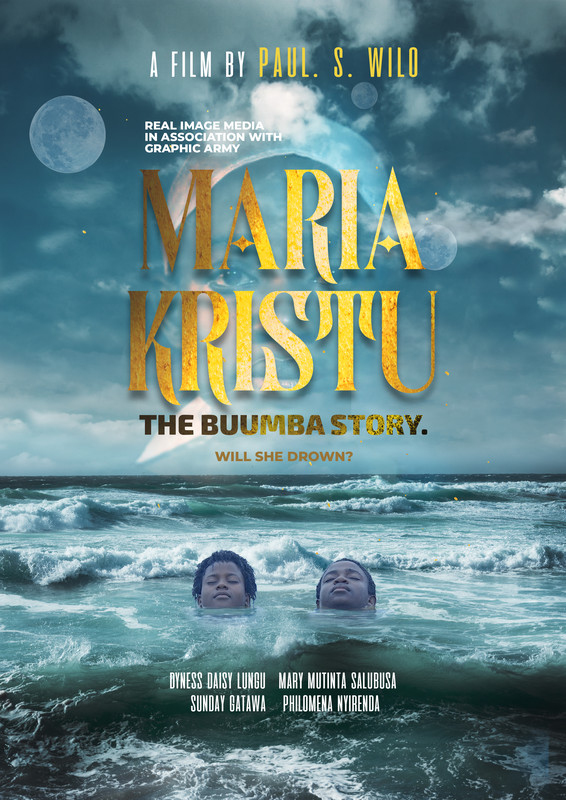

FOREIGN LANGUAGE FILM

MARIA KRISTU: The Buumba story by Paul.S. Wilo (Zambia) – Winner

NOMINESS:

- NYARA “The Kidnapping” by Ram Ally K (Tanzania)

- SHUJAA WETU (OUR HERO ) by Tom Johns (Tanzania)

- FURROWS by Julio Mazarico (Spain)

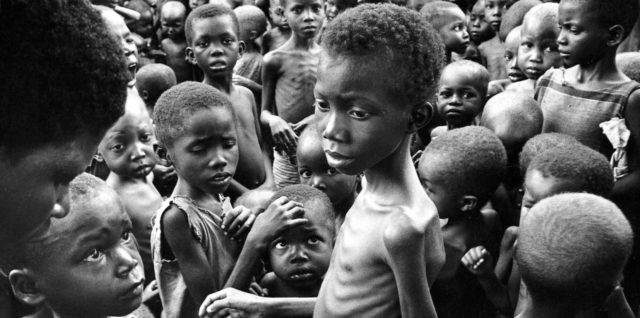

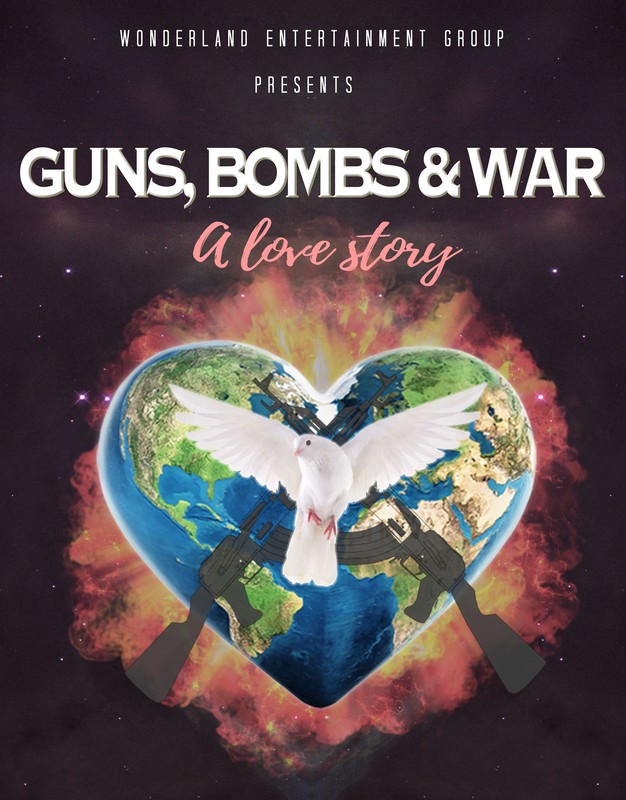

FEATURE DOCUMENTARY FILM

GUNS, BOMBS & WAR: A LOVE STORY by Emmanuel Itier from (USA) – WINNER

NOMINESS:

- GOLDEN FISH,AFRICAN FISH by Thomas Grand, Moussa Diop from (Senegal)

- FREE PLAY by Ivan Torres (Spanish United Kingdom)

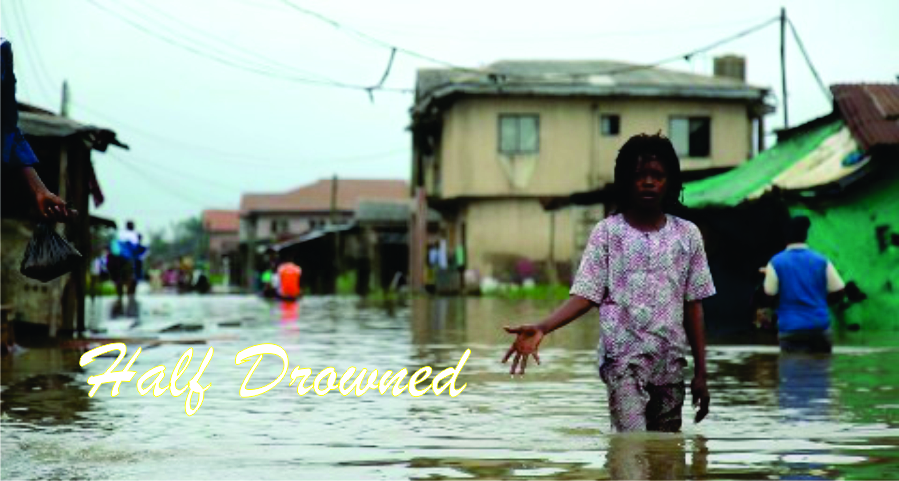

SHORT DOCUMENTARY FILM

HALF-DROWNED Nnadi Hillary Ikenna (Nigeria) – WINNER

NOMINESS:

- YABÁ by Rodrigo Sena from (Brazil)

- ARCTIC by Josu Venero, Jesus Mari Lazkano from (Spain)

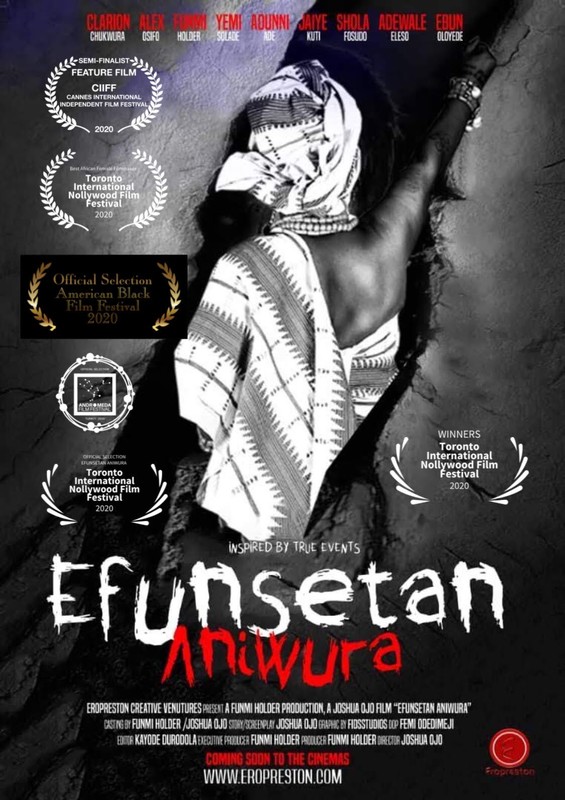

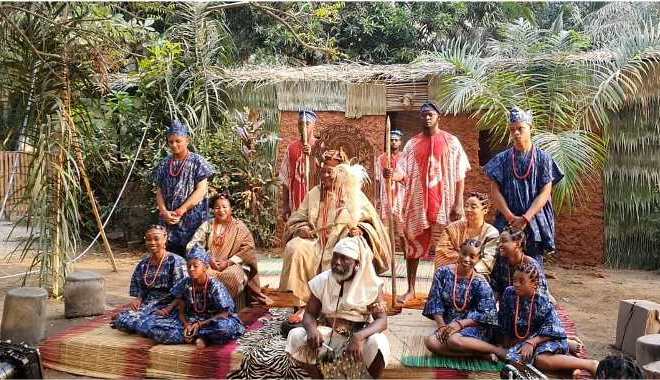

INDIGENOUS FILM CATEGORY

EFUNSETAN ANIWURA by Joshua Ojo (Nigeria) – WINNER

NOMINESS:

- ISHI ANYAOCHA by Jhonpaul Nwanganga (Nigeria)

- THE WIDOW’S SON – HAUSA VERSION by Willie Workman Oga (Nigeria)

- GRAVE by Adeshina Abiola Paul (Nigeria)

- Best actor indigenous film – YEMI SOLADE – Movie EFUNSETAN – WINNER

- Best Actress indigenous film CLARION CHUKWURA Movie EFUNSETAN- WINNER

- Best Supporting Actor indigenous film – WALE ELESHO- Movie EFUNSETAN–WINNER

- Best Supporting Actress indigenous film – JESSICA RAYMOND Movie – THE WIDOW’S SON – HAUSA VERSION. – WINNER

BEST TELECOM COMMERCIAL AWARD

AIRTEL ‘RAINMAKER’ – WINNER

NOMINESS:

- MTN ‘Music Time Traffic’

- AIRTEL

‘Know Your Size Tailor’

BEST FOOD & BEVERAGES COMMERCIAL AWARD

- MALTINA – WINNER

NOMINESS:

- SMOOV

- Hollandia

BEST SOUNDTRACK COMMERCIAL AWARD

EMZOR ‘PARACETAMOL’ – WINNER

NOMINESS:

- SMOOV

- MTN ‘Music Time Traffic’

- Airtel Know your Size Tailor